A famous font feud, music from beyond the grave, and the ideology trap

Appropriate appropriation

Ever heard of cultural appropriation? It’s the use of elements of a minority culture by members of the dominant culture, often without understanding, respect, or acknowledgment of the original context and significance. It can involve the exploitation of traditions, customs, fashion, symbols, language, or artistic expressions.

Even if we narrow down the scope of cultural appropriation to twentieth-century music, multiple genres such as rock and roll, blues, jazz, and hip-hop include instances where white artists gained mainstream success and financial benefit from genres created by Black artists, often without proper credit or recognition. It wouldn’t be a stretch to claim that Western popular music is nothing but cultural appropriation. Is that the fault of Elvis Presley, Led Zeppelin, and Vanilla Ice? Of course not – they operated within an industry and a wider capitalist system that has fine-tuned extraction without adequate remuneration.

But what if we widen the focus... What does appropriation really mean? Is it simply theft? Corporations such as Google, Microsoft, and OpenAI have populated their generative AI databases with words and images that have been “scraped” (i.e. copied) from the internet. A slew of lawsuits are currently wending their way through the US court system, alleging that the aforementioned companies (and others) have contravened copyright law by ingesting protected works. Is this simply theft, or is it appropriation?

Appropriation is about taking an element, feature, or item without asking permission and then presenting it as your own. It’s actually worse than theft. Stealing the Mona Lisa is one thing. Stealing it and then saying that you painted it is quite another. But this is what is happening with Large Language Model chatbots (LLMs) and AI image generators. Last month’s roll-out of improved image capabilities for ChatGPT provoked a craze for “Ghiblification”, or instantly rendering well-known photos or memes in the meticulously hand-drawn anime style of Japan’s Studio Ghibli, the producer of beloved films such as Spirited Away and My Neighbor Totoro.

The only way to generate these images is to tell ChatGPT that you want to produce a Ghibli version of such-and-such photo. The output is (according to OpenAI) a non-copyright-infringing artwork that the user is free to share as their own creation. This might have been old-school cultural appropriation if Studio Ghibli wasn’t itself owned by a large corporation from a dominant culture. But Ghibli is only a single widely-publicized example. Anyone can perform cultural appropriation using AI with a few clicks on a keyboard.

Black artists have borne the historical brunt of cultural appropriation, so I decided to run a little experiment as I was writing the previous paragraph. Take a famous Black visual artist and prompt ChatGPT to produce a remix of an iconic work by a famous white painter in the Black artist’s style. Dear internet, I give you Picasso’s Guernica in the style of Jean-Michel Basquiat:

This kind of activity involves a similar degree of appropriation that Led Zeppelin perpetrated when they released their versions of Whole Lotta Love, The Lemon Song, and You Shook Me without initially crediting the original songwriters/performers Willie Dixon, Muddy Waters, and Howlin’ Wolf, acknowledging the band’s debt to a slew of Black blues artists, or compensating less financially secure artists who influenced their music and fuelled their success.

Hold on a minute… have I appropriated Black culture by creating the image above? No, because I’m telling you what I did, rather than claiming that it’s all my own work. Has OpenAI appropriated Black culture by building a database that produced the image? Sort of, but not really. What the company clearly is doing is copying a specific artist’s style without attribution (since users are free to use their images without attribution).

Maybe we need a new definition of appropriation. And it doesn’t have to fit within any legal codes to be morally and socially applicable. Appropriating a style, whether personal or cultural, is wrong. The corporations that own AI tools need to do better: to give back to the people and communities that they are profiting from without so much as a polite request for permission.

To be clear, cultures evolve by reimagining, reinterpreting, and remixing everything that has preceded the current moment. This isn’t a problem if the input comes from their own or another non-dominant culture – it’s how human societies flourish. But flip the script, and flourishing turns into smothering. The dominant culture sucks the life out of less prominent cultures. This sounds vampiric, except that vampires traditionally don’t continue sucking after the first bite. Cultural appropriation involves keeping the victim alive so that it can keep creating cool stuff. And if the victim protests, watch out: you’re in for a “culture war”. The dominant culture (whether it be white, western, or male) hates seeing their dominance slip by even the slightest degree. Why? Because the people with a stake in it are incredibly insecure. Of course they are – they’ve stolen a huge chunk of their identity and they have to keep subjugating the victim at a safe distance while keeping it alive.

So if you use AI to create a work in the style of another person or culture, please, please provide appropriate credit and say thank you for their hard work. Because you barely lifted a finger.

Cerebral composing

American composer Alvin Lucier is composing new music from beyond the grave. Before passing away in 2021, the pioneer of experimental music agreed to let a small team of artists and scientists, “the four-headed monster,” experiment with the Revivification of his brain after his death. Using his blood, the four-headed monster reprogrammed Lucier’s blood cells into stem cells and used them to grow cerebral organoids, small clusters of cells that act like a mini-brain. At the Art Gallery of Western Australia in Perth, Lucier’s two organoids, unassuming and tiny white blobs, are raised on a glass plinth for visitors to observe as they compose music in real-time. Neural signals are captured from the organoids by electrodes that signal mallets to strike the 20 brass plates installed on the walls of the room, producing music in real time.

The organoids don’t only produce their own music, but theoretically respond to the voices and sounds around them. Microphones pick up gallery sounds, convert them to electrical signals, and feed them back into the mini-brain, meaning that the music ought to change in response to sounds in the gallery. The Revivification exhibition runs from April to August, and in the unlikely event I end up in Perth before the fall, maybe I'll whistle a few bars of Down Under to see whether Lucier's brain blobs can produce some posthumous pop from Australia’s most famous earworm.

Melted cheese and melted hearts

Macaroni necklaces are a pure symbol of a young child’s love on Mother’s Day, but lose their sparkle after the gift-giver passes the age of about 8. Cue a golden macaroni necklace, made with real 14k gold on a 16-inch gold chain, courtesy of Kraft Mac & Cheese and Ring Concierge. Though Ring Concierge has eye-melting prices, Kraft was dedicated to the accessibility of this delightfully cheesy present, which only costs $25 and comes with a bonus box of Kraft Mac & Cheese.

The necklaces were released on Ring Concierge’s website on May 1, but are likely all sold out now, since the webpage is inaccessible. But this successful campaign begs the question: what other nostalgic childhood gifts can be upgraded into elegant presents for adult gift-givers? With Father’s Day around the corner, it's time to prototype golden socks, or, well, whatever else it is dads want.

Puppets for the planet

A herd of life-sized animal puppets is travelling across Africa and Europe to demonstrate the displacing effects of the climate crisis. The Herd, a public art exhibit by London-based nonprofit The Walk Productions, comprises puppets of animals native to Africa, Europe, and Scandinavia, on a 20,000km journey that will culminate in the Arctic Circle in August. As they flee climate disaster, the parade grows as it goes, with local volunteers trained to build more animal puppets to add to the herd, and instructions and printables available on their website for anyone interested in making their own origami animal puppets.

The Herd brings the immediacy of the climate crisis to life, not merely sticking to facts and figures, as other climate campaigns tend to do. It’s so effective because it engages people through artistic novelty and the chance to create and interact with the exhibit themselves, evoking awe for what is not a distant and remote problem, but a pressing and personal reality for everyone on the planet today.

Leor Zmigrod, political psychologist and neuroscientist

“We possess beliefs but we can also be possessed by them.”

Leor Zmigrod studied at Cambridge and has held visiting fellowships at Stanford, Harvard, and both the Berlin and Paris Institutes for Advanced Study. Her first book, The Ideological Brain, came out this spring with the subtitle The Radical Science of Flexible Thinking. It draws on cutting-edge research to explore the deep connections between political beliefs and the biology of the brain. If you know someone who seems stubbornly fixed in their view of the world in the face of all evidence (whether on the right or the left), Zmigrod’s work might help you understand how the complex interplay between cognition and environment predisposes some individuals to inflexible ways of thinking.

What’s wrong with ideology? After all, Donald Trump is notably ideology-free, and that doesn’t exactly seem like a great way to go! According to Zmigrod’s publisher, “Ideologies offer a shortcut, providing easy answers, scripts to follow, and a sense of shared identity. But ideologies also come at a cost: demanding conformity and suppressing individuality through rigid rules, repetitive rituals, and intolerance.”

Zmigrod explained in a recent interview, “What we see with this science … is that the degree to which you espouse really dogmatic, ideological beliefs can get reflected in your body, in your neurobiology, in the way in which your brain responds to the world at very unconscious levels, and so it becomes a part of us. There’s a kind of echoing of your thought patterns, not just in politics, but they become part of how you think about anything in the world.”

Mood music makes moolah

If you use Spotify, you’ve probably seen a ghost. Or at least, heard one. “Ghost artists” (also called fake artists) first hit the music industry headlines in the summer of 2017. A rumour emerged that Spotify was flooding certain playlists with music from artists that nobody had ever heard of. What was going on?

It turned out that the tracks populating playlists such as Ambient Chill (you know, vibey background music for studying or reading) were being churned out by a small number of anonymous Swedish production companies masquerading as genuine artists. This stock music was commissioned and acquired by Spotify as part of the company’s Perfect Fit Program, designed to keep listeners hooked while paying out lower royalties than the percentages typically owed to major artists.

Music journalist Liz Pelly’s new book, Mood Machine – the Rise of Spotify and the Costs of the Perfect Playlist, explores the music-as-commodity trend that, although providing a paycheck to journeyman musicians who could do with a few extra bucks, also helps drain the colour, artistry, and passion out of music. And now – guess what? – AI-produced tunes are taking over Spotify’s playlists and making them more generic while giving even less back to human creators. If you’re interested in learning how the enshittification of music is a race to the bottom, read this excerpt from Pelly’s book that appeared in Harper’s magazine earlier this year.

Famous font fuels feud

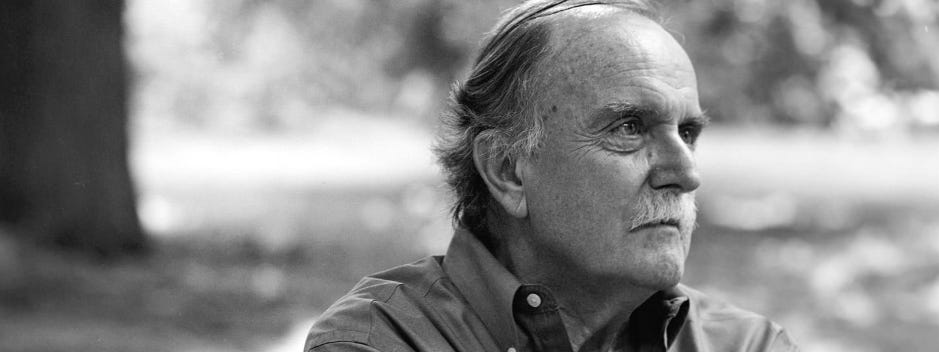

Journalist and author Tim Harford first rose to prominence by penning the long-running Undercover Economist column for London’s Financial Times newspaper. His always-fascinating Cautionary Tales podcast, which debuted in 2019, weaves “stories of human error, of tragic catastrophes and hilarious fiascos.” The most recent episode, called Dangerously near to absolute perfection, tells the uniquely hubristic story of an early 20th-century typeface so beautiful that it made enemies of the close friends who developed it, and then lay hidden by the muddy waters of the River Thames for almost a century.

Harford tells the story of font designer T.J. Cobden-Sanderson, a perfectionist who couldn’t bear to see his founding partner at Doves Press, Emery Walker, superficially skimming proof sheets before they went to print instead of meticulously checking every letter and piece of punctuation. When their business relationship dissolved, Cobden-Sanderson vindictively decided that if he couldn’t oversee the perfect typeface, nobody should have it. On hundreds of separate trips throughout 1917, he dropped the master typeface matrices and metal pieces from Hammersmith Bridge into the river below, thinking they would never be seen again.

But in 2015, around 150 of the pieces were recovered from under the bridge by slightly obsessive English typographer Robert Green. The Doves Press typeface has now been revived by Green, and is available for online and print applications.

Hiatus heads-up

We’re approaching Discomfort Zone’s second anniversary and it’s time for the first extended hiatus. As you probably know, I took up the position of Head of Creative Services at the National Film Board of Canada last October. It’s a complex, rewarding job and it means that my time is often stretched with newsletter publication weekend rolls around again. So the next issue will mark two years with barely a break and I’ll then take the summer off. I’d love to hear your thoughts. Should I change formats? Should I keep the format and change the publishing schedule? Let me know by commenting directly in the Substack app or drop me a line by emailing me at john@johnbdutton.com.

FOMO food research and writing by Silvia Todea, editing by John Dutton.

Legal disclaimers:

All images in this newsletter that are not the property of the author are used with permission or reproduced under the fair use provisions of the Canadian Copyright Act while giving appropriate credit.

The content published in this newsletter represents the private views and opinions of John B. Dutton and are not in any way connected to his role with the National Film Board of Canada.